In ‘Your Screen is Secretly 30 Years Old’ video on The Science Asylum channel, Nick Lucid argues that 7-bit colour depth is sufficient for screens, claiming that 2 million colours (vs 16 million at 8-bit colour depth) ‘would be more than enough for most people’:

Can screens make fewer [than 16 million] colours without us noticing? The answer is absolutely yes. 16 million is an overkill. 2 million would be more than enough for most people. It’s just that controlling a screen with 16 million colours costs the same as the screen with 2 million because they use the same number of bytes.

This article interrogates that statement. To provide a visual baseline, Fig. 1 compares two grey gradients: one uses 8 bits per component (bpc) while the other uses 7 bpc. Fewer colour discrete levels lead the 7 bpc gradient to exhibit clearly visible banding (where rather than smooth transition between colours, places where colours change can be identified) immediately undermining the premise that 7-bit colour depth is perceptually indistinguishable from higher bit-depths. Fig. 1 Grey gradients using different colour depths. Each goes from colour #10 10 10 to #7f 7f 7f but use different quantisation. The top gradient uses 112 distinct grey levels while the bottom one only 54.

Fig. 1 Grey gradients using different colour depths. Each goes from colour #10 10 10 to #7f 7f 7f but use different quantisation. The top gradient uses 112 distinct grey levels while the bottom one only 54.

Distinguishable shades of grey

How apparent the banding is depends on display device, viewing conditions and individual colour sensitivity. To establish an objective measure, we must consider the just-noticeable difference (JND) metric. JND is the amount a stimulus must change before the difference is detected half the time. The National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) have established a rigorous mathematical framework for calculating the JND index shown in Fig. 2.1 A JND difference of one or above indicates that the two luminance levels are distinguishable by the average person.$$ \begin{align*} j(L) &= 71.498068 \\ &+ 94.593053 \cdot \log_{10} L \\ &+ 41.912053 \cdot (\log_{10} L)^2 \\ &+ 9.8247004 \cdot (\log_{10} L)^3 \\ &+ 0.28175407 \cdot (\log_{10} L)^4 \\ &- 1.1878455 \cdot (\log_{10} L)^5 \\ &- 0.18014349 \cdot (\log_{10} L)^6 \\ &+ 0.14710899 \cdot (\log_{10} L)^7 \\ &- 0.01704684 \cdot (\log_{10} L)^8 \end{align*} $$

The sRGB colour space has been defined for CRT displays producing 80 cd/m².2 Plugging that value into the formula yields a JND index of 447. Representing this many discrete values requires a minimum of 9 bpc.

Researching practical limits in bit depth of displays, Kimpe and Tuytschaever3 found that an LCD screen with luminance ranges between 0.8 and 600 cd/m² can produce 720 shades of grey that humans can perceive as different. To encode that many colours 10 bpc is required.

Furthermore, to render smooth transitions the number of available colours must be further doubled since the goal of a gradient is for adjacent colours not to be distinguishable. To sum up, not even 30 years ago, 7-bit colour depth was sufficient to encode all colours that the average person could perceive.

Can you spot the difference?

Below is a game testing how good the player is at identifying differences in colours. It displays two rectangles — one inside the other — with the player tasked to determine whether they are the same colour. Game mode can be picked with radio buttons at the top. In 7 bpc mode only even colour values are considered (e.g. #28 6e 04 compared against #28 6c 04); in 8 bpc mode all colour values are in play.

Colour gamut

The shortcoming of 7-bit or even 8-bit colour becomes even more evident when moving beyond the sRGB standard. The transition to a wider gamut like P3 or Rec. 2020 exacerbates the quantisation problem. With colour primaries moving further apart within the xy chromaticity diagram, the same number of steps is effectively stretched, increasing the distance between available colours.

The push for wider gamuts isn’t just a marketing gimmick; it is an attempt to cover more of the visible colours that exist in the physical world. As shown in Fig. 3, sRGB misses a significant portion of the cyans and greens found in nature. To accurately represent a sunset or a deep forest canopy, a wider gamut is necessary. However, if we increase the gamut we also need to increase the bit depth.Fig. 3 CIE 1931 xy chromaticity diagram comparing colour gamuts of various RGB colour spaces.

If bit depth is unchanged, colour values in a wider gamut move further apart than they are in sRGB space, rendering banding glaringly obvious and distracting. This is the primary reason why Rec. 2020 requires a minimum of 10 bpc.4 Fig. 4 demonstrates how gradient quality degrades if the bit depth doesn’t increase in tandem with widening of the colour gamut. Fig. 4 Green gradient in sRGB, P3-D65 (using sRGB transfer function) and Rec. 2020 colour spaces limited to 8-bit colour depth. Due to differences in colour gamut, the gradients have 112, 60 and 54 stops respectively even though they all start and end at the same colour.

Fig. 4 Green gradient in sRGB, P3-D65 (using sRGB transfer function) and Rec. 2020 colour spaces limited to 8-bit colour depth. Due to differences in colour gamut, the gradients have 112, 60 and 54 stops respectively even though they all start and end at the same colour.

The claim that ‘2 million [colours] would be more than enough for most people’ ignores not only the established state of display technology but also its trajectory. The newer standards try to minimise the quantisation error to a level below human perception across an ever-expanding range of vibrant, high-saturation colours. In this context, 8-bit is already pushed beyond its physiological breaking point and 10-bit is the emerging standard.

Cost of 8 bits

To justify why 8-bit colour depth became so common, the video argues that cost of using 7 bpc and 8 bpc is the same. Computers operate on 8-bit bytes so using 7 bits per colour components would, the argument goes, ‘waste’ a single bit (or three bits per pixel). This is however a simplistic view. The technical justification presented in the video lacks comprehensive historical analysis and considerations outside the computer software.

Firstly, hardware supporting colour depth which did not fit evenly into bytes did exist. Sega Genesis used a 3-bit colour depth and wasted 7 bits per entry in its colour palette. Amiga organised graphic data in bit-planes which allowed colour palettes of arbitrary size; meanwhile colours in palette were stored ‘wasting’ 4 bits per entry. It also wasn’t unusual to use high-colour mode with 5 bpc resulting in a wasted bit (although, a 5-6-5 variant of high-colour mode was also available).

Secondly, even if memory costs of 8 bpc and 7 bpc are the same, the processing cost is not. Higher bit-depth requires more complicated (and thus expensive) digital-to-analogue converters (DAC) and larger gamma conversion look-up tables (LUT). Furthermore, digital connectors such as DVI could take advantage of reduced bandwidth requirements if they only needed to send 7 bits per channel. DisplayPort from its inception supported 6-, 8-, 10-, 12- and 16-bit colour depths, without worrying about 8-bit alignment.

It’s hard to dispute that computers using 8-bit bytes had an impact on 8-bit colour depth becoming so popular, but that’s not an argument in support of a claim that 7-bit colour depth is all that majority of people need. The video used the size of a byte to justify its conclusion without analysing all the historic solutions or costs and benefits outside ‘it fits the byte’.

Non-reproducible colours

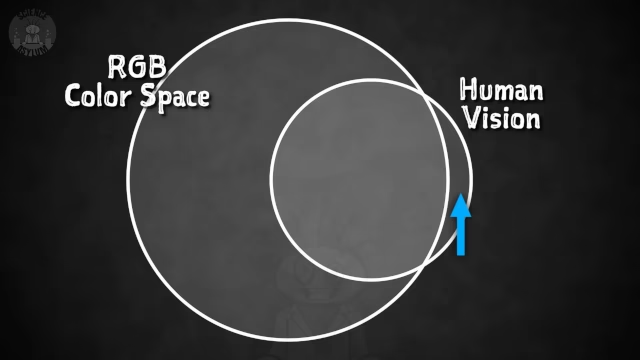

On a final note, at 2:15 mark in the video, Nick Lucid compares the RGB colour space with human vision. Difference in both is represented by a Venn diagram as seen in Fig. 5. The video offers no explanation for this graphic, leaving its meaning a mystery to be solved. Fig. 5 A screen grab from the ‘Your Screen is Secretly 30 Years Old’ video showing a Venn diagram of colours defined by RGB colour space and colours recognisable by humans. The arrow indicates colours which humans can see but RGB colour space cannot describe.

Fig. 5 A screen grab from the ‘Your Screen is Secretly 30 Years Old’ video showing a Venn diagram of colours defined by RGB colour space and colours recognisable by humans. The arrow indicates colours which humans can see but RGB colour space cannot describe.

The obvious interpretation is that RGB colour space used by monitors can define colours which are not perceivable by the human eye. This is a fundamentally flawed notion. Colour spaces designed for displays (such as sRGB, P3 or Rec. 2020) describe a strict subset of visible colours as illustrated in Fig. 3.

sRGB in particular covers only about a third of the xy chromaticity diagram. This reality is hard to reconcile with the graphic in the video. While sizes in Venn diagrams don’t need to indicate anything, by using circles of unequal sizes, Nick Lucid seems to convey that there’s only a small sliver of perceivable colours that RGB colour space does not cover. In reality, there’s twice as many colours sRGB cannot represent as those that it can. The diagram in the video is quite misleading indeed.

Then again, the diagram wasn’t well explained in the video so it’s not clear what it actually means. The most charitable interpretation I could think of is that Nick Lucid tried to convey the incorrect observation that 8-bit colour depth leads to 7/8 of the colour space being indistinguishable. Although that still doesn’t explain why the intersection between RGB colour space and human vision is so much larger than portion unique to human vision.

Conclusion

The Science Asylum is a channel with an assortment of educational videos on physics. Unfortunately, the foray into technology video was a miss. The ‘Your Screen is Secretly 30 Years Old’ video has been made to fit a preconceived conclusion rather than to explore the colour theory and the future of computer display technologies.

The claim that 7-bit colour depth is enough is trivial to debunk with an image editing software. The history of computer displays is cherry-picked and focused on aspects which support host’s claim. The video lacks discussion of wide colour gamuts which exist to better represent real world. All in all, most information in the video is wrong or at best misleading.

As a long-time admirer of The Science Asylum, it is disheartening to see such a badly researched video on the channel.1 1998. Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM). Supplement 23: Structured Reporting. National Electrical Manufacturers Association, Rosslyn, VA, USA. ↩

2 1999. CEI/IEC 61966-2-1. Multimedia systems and equipment — Colour measurement and management — Part 2-1: Colour management — Default RGB colour space — sRGB. International Electrotechnical Commission, Geneva, Switzerland. ↩

3 Tom Kimpe, Tom. Tuytschaever. 2007. Increasing the Number of Gray Shades in Medical Display Systems — How Much is Enough? Journal of Digital Imaging, Vol. 20, № 4 (December), 422–432. doi:10.1007/s10278-006-1052-3 ↩

4 2015. Recommendation ITU-R BT.2020-2. Parameter values for ultra-high definition television systems for production and international programme exchange. International Telecommunication Union, Geneva, Switzerland. https://www.itu.int/rec/R-REC-BT.2020-2-201510-I/en ↩